Despite continuing clashes over the last 40 years, the ongoing conflict between West Papua and Indonesia remains largely unknown to the public.

Press freedom in West Papua is low, and independent media voices are often silenced. The few reports that do manage to reach a wider audience tend to frame the conflict around the political struggle for independence, or emphasise the more violent aspects of the conflict.

In 2011-12, EngageMedia and Justice, Peace and Integrity of Creation collaborated with local organisations in Jayapura and Merauke to teach Papuan activists video production and distribution skills. With these skills, activists were able to document the stories of daily life in West Papua: the struggle for equality and dignity, better access to education and environmental protection.

Their efforts were documented on the Papuan Voices website, one of the first of its kind. The videos they recorded and produced have achieved international visibility through the dissemination of Study and Screening guides, designed for use in classrooms and community contexts.

Monitoring and documenting

With the development of internet-enabled mobile phones and streaming technology, the act of digital vigilance has now been democratised. Advocates and activists of all types are taking advantage, using this technology to turn the tables on governments, institutions and corporations. From monitoring elections to recording police brutality, citizens are now equipped with all kinds of tools which enable them to gather and disseminate information exposing wrongdoing and demanding transparency. This section will discuss different ways you can collect data, document happenings or seek information in the context of advocacy work.

Why use it?

Collecting information in a concise and targeted manner provides you with raw support materials on which to base your work, lending your organisation credibility and providing you with a running archive of your work.

Implicit in the act of documenting is the act of monitoring – of recording for posterity and accountability. By becoming a content producer, you are -- most importantly -- reversing the natural order of information-flow from top-down to bottom-up. Producing your own content means giving your constituency a voice, and taking control of what you express, upsetting traditional structures of media dominance. This is the basic concept behind citizen media and community media -- putting the power of media creation and information control back in the hands of citizens and the community.

You can collect or document information by:

- surveying your constituency or target audience

- using a digital recording device – a video camera, a still camera, an audio recorder

- searching for existing data or content online

- making a request for data from the relevant public or government office

- creating an interactive platform inviting people to submit their own information (see our chapter on engaging communities in participatory projects and crowdsourcing)

Public bodies operate with public money. Their role is to serve members of the public and the information they create and hold belongs to the public. National and international law recognises that members of the public have a fundamental right of access to information from public bodies.

Even if your country doesn’t have an ‘access to information’ law (called ‘Freedom of Information Act’ or ‘Right to Information Act’ in some countries), there are likely to be some provisions which require public officials to answer requests from the public. Here is a link to a full list of the countries with access to information laws.

The right of access to information operates in two ways:

- Proactive: public bodies are under an obligation to provide, publish and disseminate information about their main activities, budgets and policies.

- Reactive: all people have the right to ask public officials and bodies for information about what they are doing and what documents they hold.

Collecting data online

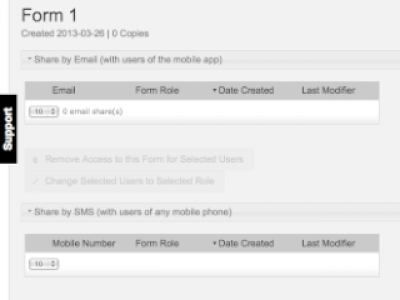

Google has a good set of data collection tools integrated into its Google Drive suite. The 'Forms' function allows you to create customizable surveys or lists that are automatically formatted into a spreadsheet. Other services like Surveymonkey or Ushahidi use a more sophisticated interface but allow you to publish or present information in more complex ways. Crowdsourcing, or outsourcing part of the task of information collection to your constituents, is also an increasingly effective way of collecting data. Magpi is a tool that allows you to create and collect information through mobile phone surveys.

Curating content, or manually compiling content off of blogs, twitter feeds, or videos, is another popular way of collecting data, especially data that cannot be easily parsed by machines. Emergency Journalism has published on their website a good list of content curation tools.

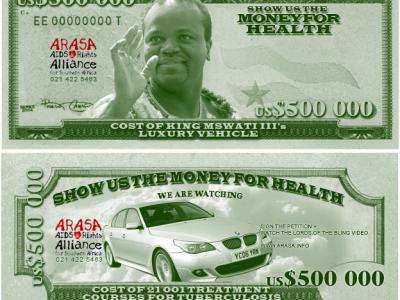

Citizens also have the right to demand that certain information be made public: figures on government spending, or census statistics, for example. Under Freedom of Information law, the authorities are obliged to respond. WhatDoTheyKnow, a website created by MySociety, allows users to make requests for information of UK government and public bodies. Once these requests are made, they are posted on the site in searchable form for others to read and explore. The site has been very successful at bridging the gap between citizens and an often opaque bureaucracy. At the time of writing, over 150,000 requests had been made by over 30,000 users.

Transparent Chennai is another site that aggregates data from government and independent sources to help community workers identify the areas in Chennai most in need of basic amenities. Official data often stands in stark contrast to crowdsourced data showing the reality on the ground.

Visit Tactical Tech's own Drawing by Numbers site for an in-depth look at some of the tools and techniques of data collection for advocacy work.

The concept of 'sousveillance' has gained traction over recent years. Initially coined by Steve Mann, a professor at the University of Toronto, the term describes the "inverse of surveillance", as conducted by ordinary citizens.

The idea of the citizen as monitor is not a new one, however. In 1991, a bystander videotaped the Los Angeles Police Department's brutal beating of a young man called Rodney King. The video was seen by millions of people around the world and used as evidence in a court case against the police officers concerned. It also inspired the creation of WITNESS, an organisation aimed at empowering citizens to use video for human rights.

In the act of bottom-up monitoring lies an inherent capacity to subvert power. “There is more of a bi-directionality with sousveillance. Surveillance is corrosive to society. The presence of sousveillance reduces the need for surveillance. In a sousveillance society, people can know what everybody's up to,” Mann explains.

In 2012, Chinese political artist Ai Wei Wei used this in a poignant act of defiance against the Chinese government. By setting up a simple system of home webcams, he was able to broadcast his life under house arrest to the public, thereby cleverly inverting the government's own surveillance of him. When anyone could monitor him day and night, the need for surveillance was rendered redundant.

Source: 10 Tactics

Recording media on your own

Documenting through multimedia is the first step towards creating a pool of content on which to base your campaign or project. The more focused your approach, the clearer your vision of the end result will be – and that means less work, as well as less wasted time at the production and editing stages. The fact of documenting can be an end in itself - simply to record truthfully an event as evidence or turn the camera on the watchers can be a strong political act. But you will multiply tenfold the impact of your content by sharing or developing it. Think of what the content could be used for:

- for an archive or a searchable database

- for posterity / monitoring purposes (see our chapter on documenting on the go)

- as source material for a digital story (see our chapter on digital storytelling)

Depending on your ultimate goal, the way in which you document and what format you use will vary. In all cases, especially when recording in a monitoring context, the accurate logging of the time and date is crucial. For an archive or database, the most important thing is that your content be searchable. This implies the development of a system to parse the content with keywords and split it into manageable chunks. Sites such as Soundcloud allow you to tag audio content with keywords and leave comments at specific points in the audio track. Photo sites like Flickr also allow you to search images based on user-generated keywors.

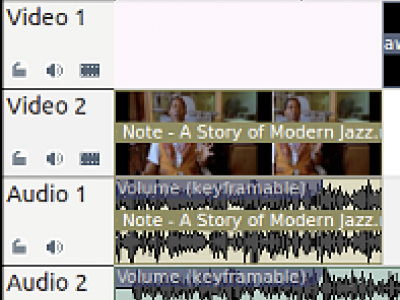

When recording video for a digital story, consider carefully the tone, length, and kind of story you want to tell and plan accordingly. For fictionalised stories, you may want to storyboard your shots - that is, outline them in sketches on paper beforehand. Your challenge then becomes the task of matching your shots to your storyboard. For documentaries, the tendency is to document as much as you can - long-form interviews, contextual shots, action footage - and cut down the excess in the editing room to let a story emerge. There is no one right way or wrong way to go about documenting your reality; but there are a few few guidelines you can follow to make things easier.

Some tips to remember when recording media

Practical Tips for Video - Recording, converting, editing and distributing your video

Practical Tips for taking photos

Case Studies

In 2007 and 2008, the Targuist Sniper caused uproar after he captured and posted videos on Youtube showing several police officers in Morocco accepting bribes from car and truck drivers on the road. His videos were viewed over 1.7 million times, prompting the Moroccan government to enforce large-scale fines on his town in an attempt to pressure him to stop his activities. Similarly, IamJan25.com is a web repository of images and videos captured during the Egyptian uprising, and stands as a potent record of unfiltered eye-witness accounts captured by demonstrators in Tahrir Square.

Local NGO Janaagraha, based in Bangalore, created 'I Paid A Bribe' to foster a culture of whistleblowing in India -- a country where citizens are expected to pay bribes to government officials for anything from a driving licence to a rations card. The website allows people to anonymously report their stories (written or recorded on video) of instances where they have either paid a bribe, or declined to pay a bribe when offered. The data is then analysed, revealing which government departments are the most corrupt.

TheyWorkForYou is a website created by MySociety that aggregates content from various UK parliamentary records with other data, such as the election records of MPs, which is publicly available. The site allows UK citizens to connect with the Members of Parliament in their country, read debates, and monitor what their local representative is doing in their name. Following a scandal in 2009 when the government sought to have MPs’ expenses claims kept secret, MySociety mobilised voters to send a few thousand individualised emails to MPs demanding transparency in the use of public funds. Soon after this campaign, the UK government agreed to disclose data on MP expenses.

The Alternative Asean Network on Burma (ALTSEAN-Burma) 2010 election watch created a no-frills website to provide background information, analysis, and up-to-date information on the 2010 Burma elections. The format was concise and user-friendly, for activists, media, researchers, legislators and policy-makers. The overall aim of the project was to monitor whether the electoral process was being conducted in a free and fair manner.

Farmsubsidy.org uses Freedom of Information Act requests to compile information on farm subsidy funds from government sources in every EU member state. They make this data publicly available, allowing users to create their own lists to investigate where the money went and draw their own conclusions. A similar initiative in Slovakia, called Fair Play, gathers invoices and other documents that show how the Slovakian government spends its money. This material is then added to a database connected to the Fair Play website, and people are invited to use this information to influence political change.

Further Resources

- Go to Tactical Tech's message-in-a-box filming and editing section for more tips on shooting, audio, lighting, editing and more.

- Witness, a US-based NGO promoting the use of video for human rights advocacy, has a great set of resources around Documenting and Reporting with video. Check out their PDF on Filming for Human Rights Documentation, Evidence and Media.

- The Center for Social Impact Communication has produced a guide called Communicating via imagery, which provides a framework for non-profit organisations who want to use photography as a central element of their communications strategy.

- The Creative Activism website has a good module on Documentary and Video for Change with a lot of examples.

- Digital Democracy has published a digital media training manual on basic concepts of framing and composition for photo and video.

Video Tools

Amara

Handbrake

Bambuser

Obscura Cam

Desktop Video Editors

Online Video Editors

Workthrough on creating a video mashup

Audio Tools

.png%3Fitok=rF0KWQB6)

.jpg%3Fitok=pXDTLHzY)

.jpg%3Fitok=3tJxk_zi)

.jpg%3Fitok=AIh9YY_n)

.jpg%3Fitok=1X702tBf)