Harassmap, founded by Rebecca Chiao in 2010, is the technological component of a movement designed to combat gender-based violence in Egypt. It is an interactive map that provides a place for women and other victims of sexual harassment to report instances of harassment on the streets of Cairo.

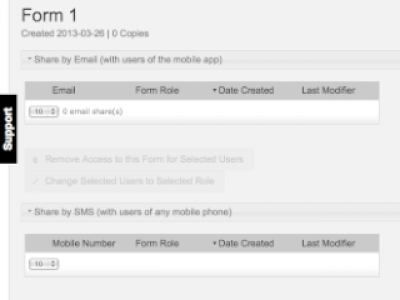

Using a number of methods to gather the information, people can submit reports via SMS, email or an online form. The reports are then put onto an online map, making the entire system act as an advocacy, prevention, and response tool, highlighting the severity and pervasiveness of the problem. Since 2010, similar initiatives have sprung up in other countries, such as the Women Under Siege project in Syria.

Crowdsourcing

Crowdsourcing is a way to delegate tasks to a group of people or foster collaboration between a group of unconnected people. It can happen online or offline, and generally relies on a public audience for contributions; one that is perhaps outside your usual network of allies.

Wikipedia and wikis in general are some of the best examples of this. Crowdsourcing is also popular as a collective funding platform (Kickstarter, Indiegogo) or as a vehicle to collect community votes.

The biggest challenge in using crowdsourced information in your campaign is the issue of verification : How can you be sure that the information submitted is trustworthy?

While there is no complete solution to this problem, there are ways in which you can alleviate the possibility of false or unusable reports. Simply put, the most reliable reports are those which are confirmed by multiple sources and collected through different types of media, supported by photo or video documentation, or corroborated by a trusted source on the ground.

It can also be useful to identify different tiers of reporters, and assign a level of trust to each. Trusted community members who have a good reputation and have given credible information over a long period time would rate higher on this scale, and unknowns would rate lower. You can even designate the recruitment of participants to certain trusted community members, who then become responsible for verifying the correctness of the reports. A mutual incentive system ensures more reliable reports.

Even unreliable reports, in certain cases, can be used as long as they are clearly marked as 'unverified'. However, in cases in which reports could defame the reputation of another person, it is best to always verify the report, and even then, anonymise all details that could potentially be used to identify either party.

For more information, consult Ushahidi's Verification Guide.

Emergency Journalism, an initiative of the European Journalism Centre, also offers a useful verification tools list and an article on 5 steps you can take to verify user-generated content. They also publish a list of crowdsourcing networks. Storyful has posted about its validation process on its blog, with some good real-life examples.

Why use it?

Ever-expanding social media networks and improved internet connectivity have made crowdsourcing a popular and accessible tool for digital activism. It allows you to amplify your message by multiplying the number of voices contributing to and spreading that message. Volunteering or donating time or money is made more manageable by the sheer number of people sharing the load.

It can also empower and embolden your community by creating a sense of identity through collective storytelling. For organisations, crowdsourcing information means that it is now easier to get data that was formerly either inaccessible or unattainable due to lack of resources. It can also serve as a publicity tool for your campaign while at the same time inviting the participation of your community.

How can I use it for my campaign?

Crowdsourcing is different from outsourcing, in that it is an open call rather than an appeal to a specific group. Any crowdsourcing initiative is based on a 'feedback loop', in which a continuous cycle of collection, verification and action assures the sustainability of your project. The basic steps in this loop are:

- Collect information – Clearly identify the kinds of information you want to collect. Set up a platform that enables a maximum degree of participation from your target community. Spread out across a range of media, both online and offline. Encourage contributions by providing incentives for community members to submit reliable information.

- Verify the information – Information collected must be verified according to criteria defined by your team and your project.

- Action and Result – Organise and publish the information within a framework that motivates those with the power, resources or responsibility to act on the submitted reports. Share the information so it trickles down, to encourage further contributions.

Collective Storytelling

Using crowdsourcing techniques to collect personal stories from the community can be an effective way to not only document an issue and ground it in real experience, but also to strengthen and define a community around that issue. The blog Uprising of Women in the Arab World is a bilingual English-Arabic site that combines personal storytelling with participative actions. Bloggers are encouraged to tell their stories through personal blog posts or express their solidarity with collective photo campaigns. Many of the posts deal with issues of gender roles or incidents of sexual harassment. Participants are united around a common cause and are able to empower themselves by exposing the prevalence of these occurrences in their own communities.

Collective creation can also be fomented by time-limited environments like Book Sprints. The goal of a Book Sprint is to produce a book from zero in 5 days. Facilitators and contributors share knowledge and resources, spurred by the team-building and intense collaboration needed to publish a book in such a short period of time.

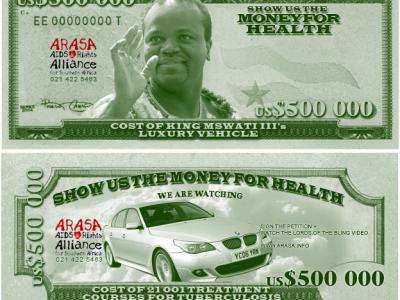

Mamdawrinch is an interactive website aimed at encouraging citizen participation in the fight against corruption in Morocco. It enables Moroccans to report acts of corruption, file complaints, and share information anonymously and in the language of their choice – Moroccan dialect, Arabic, or French.

Tarik Nesh-Nash, board member of Transparency International Morocco, was instrumental in setting up this platform, the first of its kind in the country. The information received from users can be in the form of video, pictures, or written accounts including details about where and in which sector the corrupt act occurred. This information is then published on the website, on a map, and through social media channels.

This process is less about pointing fingers and more about creating an indirect tool of pressure, says Nesh-Nash. “We have no way to verify the authenticity of the user, as well as the information there…to avoid defamation cases, we anonymise it. We remove all the names, which can create problems both for the person who sent it as well as the corrupt person.”

The tool is also supported by an integrated Anti-corruption Legal Advocacy Center (ALAC), which allows people with strong cases to request legal assistance to potentially take the issue to court.

But the project still faces big challenges – a disparity in the level of technical knowledge among users, a lack of reliable internet connectivity in some areas, and low rates of online engagement. But Nesh-Nash is confident that the site will deal with some of these problems with a bit of human-powered support. “The challenge today is not the technology – you need a team of committed people, [who are] objective and trusted by the community to do this work of validation,” he says.

“The aim of this project is not to make an accusation but rather to give examples of corruption in certain sectors. We want to open the debate online and see how we can solve this.”

Participative mapping

Interactive mapping platforms, of which the best known is Ushahidi, give a valuable geographical dimension to your crowdsourced reports, which can serve not only to clarify raw data and identify problems, but also as an important resource for workers on the ground, especially in crisis situations. Uchaguzi, a system set up to monitor the Kenyan elections, and Syria Tracker, an aggregator for crime reports and other information, are both good examples of effective use of Ushahidi-based participative mapping platforms.

However, several practical considerations should be taken into account before deploying a participative mapping project:

- Is there a definite benefit to mapping and tracking information this way? Can you use existing resources or indicators?

- How will you collect the information? Where and how do people in your community use technology, and what are their habits? Who will gather the reports – the public, or a group of trained individuals?

- What are the risks associated with collecting information on this issue? How will the information be treated or displayed once it's published?

- What will the follow-up look like? How will you take action in response to the reports submitted, and how will you measure the project's efficacy?

Mapping initiatives require careful planning and strategic forethought. Platforms that are poorly conceived or deployed too hastily will often result in what is known as a dead map: a map that never got off the ground due to lack of data or a clear goal. The Dead Ushahidi Project is a website that catalogues some of these failed maps, and can be a useful resource to consult on what not to do when implementing mapping elements in your campaign. There are also ethical concerns to take into consideration, especially around issues of informed consent and the risk of dehumanizing the problems without proper community data.

Case Studies

Kuhonga, based in Nairobi, is an online corruption mapping tool built on the Ushahidi platform. The site allows Kenyans to report incidences of corruption in real time through text message, a mobile app, email, social media, or through the website itself. The site focuses on both low- and high-level incidences of corruption in government, law enforcement, immigration and customs, educational institutions as well as businesses.

Map Kibera, Nairobi's largest slum, was nothing but a blank spot on the map before young Kiberans decided to create a free and open digital map of their community. Using OpenStreetMap, an open source mapping software, they plotted various locations and roads in the neighbourhood and supplemented it with information from residents. Map Kibera works well because it addresses a crucial issue: the scarcity of information available, and the failure of the government to provide it. Contrast this with an initiative like They Work for You, which looks at the ineptness of the government at making available information that already exists. Focusing on the problem is crucial for a successful crowdsourcing campaign.

Crowdsourcing tools are not all report-based; they can also be of the collaborative and creative type. Amara, a project of the Participatory Culture Foundation, is the simplest and best-constructed free subtitling tool of its kind. Amara is a free and open source widget that allows any viewer to easily create captions or subtitles over any video online. Your videos can reach a much wider, international audience, and invite collaboration between viewers who can volunteer to translate or subtitle all or part of a video.

Further Resources:

Read more about using crowdsourcing as a non-profit organisation in this article, entitled Harness the crowd to increase awareness, create new volunteers, and gather information for your charity.

For more information on Ushahidi, visit their resources page. This article also contains an extensive list of "maptivist" initiatives, and this post talks about the future of digital maps in global activism.

The Engine Room has produced a report on recent anti-corruption initiatives, many of which involve crowdsourcing as a principal element to their strategy. The report breaks down some examples and provides good contextual analysis into the advantages and pitfalls of crowdsourcing.

.png%3Fitok=rF0KWQB6)

.jpg%3Fitok=pXDTLHzY)

.jpg%3Fitok=3tJxk_zi)

.jpg%3Fitok=AIh9YY_n)

.jpg%3Fitok=1X702tBf)